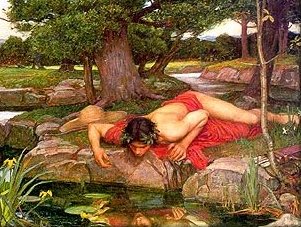

What does it mean?

Today’s management approaches are all abstractions and no humanity

Hamburger Management has a spreadsheet in place of a heart and a profit-and-loss statement for a soul. Is it any wonder that is has to resort to violent, artificial means of motivating people? Giving huge rewards to a chosen few and driving the rest by threats and intimidation isn’t motivation. Nor is using smart sound-bites and slogans. There is only one way to fill people with joy in what they do and bring out their highest abilities—and that way hasn’t changed since the human race began.Motivation is the subject of more articles and training courses than almost any other management “technique.” Yet I’m constantly appalled at the nonsense that I see written and handed out on the topic. Mostly, Hamburger Management ignores the purely human aspects of the enterprise, preferring to focus on spreadsheets, ratios, and results. It does notice motivation however—mostly, I suspect, because that seems to offer a way of getting people to work harder for the same pay or even less. Hamburger Managers are expected to motivate their people,

often by standing behind them wielding a big stick. If that doesn’t work, they stand just ahead, waving a large carrot and shifting it just out of reach each time their people get close enough to feel they might be able to get their hands on it.

This kind of artificial, carrot-and-stick motivation is a potent cause of workplace stress. It’s as if you’re in a car driven by someone who accelerates madly whenever there’s some space ahead, then stands on the brakes when they seem about to throw you headlong into something. It doesn’t make for a relaxing ride, and it’s hell on the brakes and the tires. Yet that’s the atmosphere in many organizations today: a scary ride mixing being forced to drive way too fast with suddenly being dragged to a halt when the organization decides it can’t afford what it will take to make you keep up the constant acceleration.

What all this sham motivation misses is what truly makes people love their jobs.

Meaning

People only care deeply about what they do when it gives their lives meaning and purpose. They don’t really work for money, they work for what money means to them: security, good food, pleasure, status, fun, relaxation. They don’t respond to incentives, they respond to what the incentives mean in their lives: praise, recognition, self-worth, and a sense of value from achievement. Even punishment and threats only work when they truly mean humiliation, loss, or sharp, personal pain.Managers who ignore this haven’t a hope of producing anything but the minimum effort.

Part of something wonderful

True motivation means giving people something real to care about—lasting values like truth, friendship, honor, loyalty, justice, love, and self-worth. It means letting them see why they’re doing what they’re asked to do, and how it will contribute to something they find worthwhile. Of course people want personal success and rewards. But few want these things at any price. Instead, the vast majority of folk give the highest value to the feeling that they are part of something wonderful. They want to believe that the world (or, at least, the part of it that they inhabit) cares about and values what they do.They also want to feel that the organization cares about them. Slowing down gives leaders time to explain the meaning of the work, to show its value. It also lets them that show that they care about their people.

Blood, sweat, and tears

When someone truly cares about us, we almost automatically start to care about them. All the great leaders of the past have known this. Napoleon talked personally with his soldiers and handed out medals to show them that he cared about their hurts and valued their bravery. They responded by fighting for him until the last. Winston Churchill walked in the bombed ruins of London and spoke the words the defiant people would have spoken if they’d had his eloquence. He didn’t talk about abstractions, like overall war plans or strategic objectives. He spoke about real things: blood, sweat and tears. He embodied the values the nation was fighting for. He gave meaning to people’s efforts to stay alive and fight back.Hand people instructions and they’ll do no more than you tell them to—and maybe not even that. Give them rules and they’ll find ways around them. Talk about financial ratios, profitability, and return on investment, and their eyes will glaze over. But give people something to believe in—a sense of meaning and purpose in what they do— and show them that they matter, and they’ll produce efforts and results you wouldn’t have imagined possible.

Labels: enjoying work, leadership, slow leadership