Why fear of failure is the most common blockage to success

A balanced outlook on life is more important than you think.

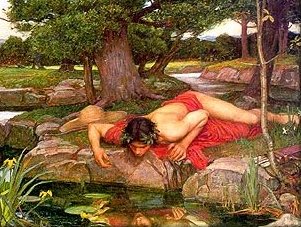

Consider this: every strength can become a weakness; every talent contains elements that sometimes make it into a handicap. Today, we’re urged constantly to be winners and to achieve high standards. If being a winner is everything, what does that make losing feel like? Attitudes like this can make people so terrified of failure that it blocks them from doing the very things that might help them become what they desire. Put simply, it ruins their lives. Here’s how it happens.Trial and error are essential to solving life’s problems and building achievement. Yet many people fail to make any trials—to change, try new things, or just to open their minds to fresh options— because they’re so afraid of making an error. They can’t accept the idea of being seen to make a mistake—even if it’s essential to find the correct answer. They draw back from trying anything new in case it might prove they’ve been wrong in the past. Their fear of risk stymies all progress.

Yet each error is the critical feedback that these people will need to start a new trial that will proceed through new errors and new trials to converge on a better solution. Making an error isn’t simply a failure. Every error is a step on the path to a success. No errors usually means no successes either.

So why do they make the mistake of believing that the error is somehow harmful to them, when it’s actually helpful? How have they become so deeply invested in protecting their egos, and in trying to replay past achievements, that they give up opportunities for a better future?

Our superstitious bosses

The answers are depressingly banal:- Highly successful people quickly tend to become superstitious. They’ve maybe never really experienced failure, so it holds a terrible fear for them. They’ll do almost anything to keep that fear at bay, from steadfastly ignoring needed change to the silly rituals some sports champions follow to “ensure” another win.

- For them, change seems to represent only the potential of failure, not the chance of greater success. They attribute their past achievements to specific actions taken then, not to a process of adaptation and improvement. It’s as if they focus so much on the moment of triumph that they forget the way they reached it. They try to freeze that blissful instant in place by repeating past actions again and again.

- They suffer the secret fear that any change might move the basis for winning into areas where they are not so strong. It’s as if a sports champion faced a change in the rules of the game. Alter those, and his or her long-practiced skills might no longer count for so much. And the very idea of developing new skills, given all the effort it took to develop the original ones, is terrifying.

- They become so used to focusing on a set path to success that they over-estimate its long-term value and dismiss the potential benefits of change. Whenever a positive value, like achievement, becomes too strong in someone’s life, it’s on the way to becoming a major handicap. It’s as if they try to freeze the current (successful) situation in place to avoid needing to make yet more effort to change with future circumstances.

The curse of unbalanced values

A sense of achievement is an extremely powerful value for most successful people. They’ve built their lives on it. They’ve always achieved at everything they do: school, sports, the arts, hobbies, work. Each fresh achievement adds to the power of the value in their lives.Gradually, failure becomes unthinkable. They’ve never failed in anything they’ve done, so have no experience of rising above it. It becomes the supreme nightmare: a frightful horror they must avoid at any cost. And the simplest way is never to take a risk by trying any other approach. Stick rigidly to what you know you can do. Protect your butt. Work the longest hours. Double and triple check everything. Be the most conscientious and conservative person in the universe.

And if you have to do anything risky—and constant hard work, diligence, brutal working schedules, and harrying subordinates won’t ward it off—use every possible means to make sure you don’t fail. Lie, cheat, falsify numbers, hide anything negative. The collapse of ethical standards in certain major US corporations has much more to do with fear of failure among long-term high achievers than criminal intent. Many of those guys at Enron and Arthur Andersen and Adelphi were supreme high-fliers, basking in the flattery of the media. Failure became an impossible prospect.

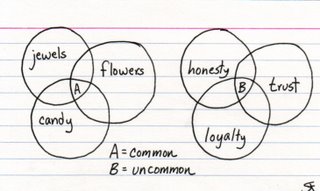

Beware of unbalanced values in your life. Beware when any one value—however benign in itself—becomes too powerful. Over-achievers destroy their lives and the lives of those who work for them. People too attached to “goodness” and morality become self-righteous bigots. Those whose values for building close relationships become unbalanced slide into smothering their friends and family with constant expressions of affection and demands for love in return.

Balance counts for more than you think. Some tartness must season the sweetest dish. A little selfishness is valuable even in the most caring person. And a little failure is essential to preserve everyone’s perspective on success.

So, are you a positive person? Maybe you need to cherish your negative side too.

Labels: corporate culture, fear, management attitudes, thinking about management